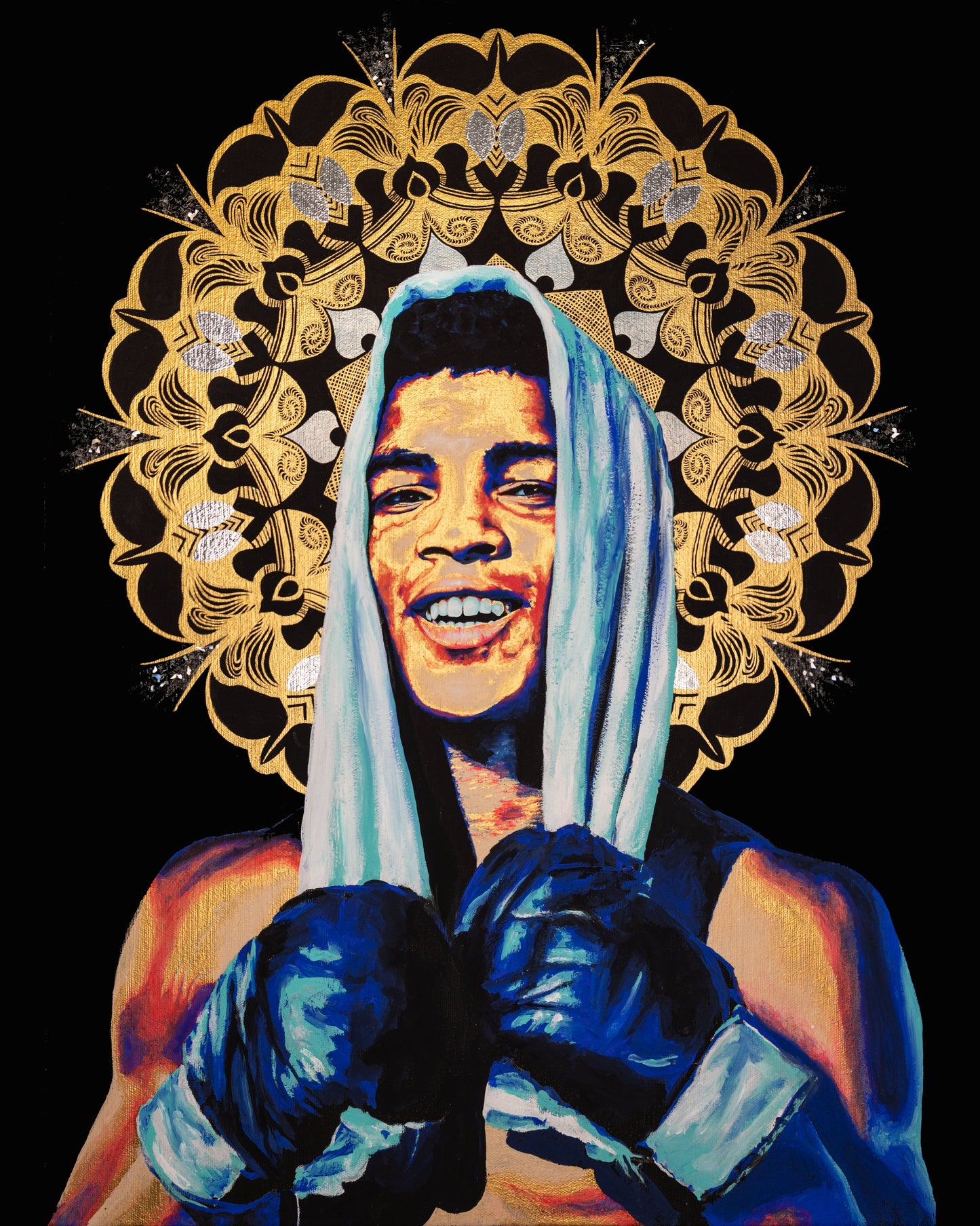

Kara Renee Art

Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali

Share

I chose to paint Muhammad Ali for Black History Month for a couple of reasons. He was born and raised in Louisville KY, my city that I love so much. He is a huge part of our local culture, and has been an incredible influence. I respect and admire that he stood for what was right before these ideas were popular. That he stood proudly against criticism and life altering consequences. There is another reason that is very personal to me. I’m not ready to share that reason publicly, but happy to talk about it one on one if you are interested in knowing. Below is a short description of just a few of his incredible contributions to the betterment of our society.

Four years before James Brown recorded “Say It Loud — I’m Black and I’m Proud” in 1968, and two years before Adam Clayton Powell Jr. and Stokely Carmichael first used the term “Black Power” within weeks of each other in the spring of 1966, Ali had become the physical manifestation of the concept. Shortly after defeating Liston on February 25th, 1964, the new heavyweight champion announced that he was changing his given “slave name” of Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali. Many sportswriters (and even some of Ali’s boxing rivals) refused to address him by his new name, continuing to call him Cassius Clay. “I know where I’m going and I know the truth and I don’t have to be what you want me to be,” Ali said at his first post-championship press conference. “I’m free to be what I want.”

In the months and years that followed, Ali transformed himself from being merely a boxing champ to a champion of his people, speaking out against injustice and racial inequality. He was frequently misunderstood by the media, which at the time was almost exclusively white (as opposed to just overwhelmingly so today).

In March 1966, after Ali’s draft status was reclassified and he became eligible to serve in the military, the champ made headlines around the world when he refused his induction into the U.S. armed forces, invoking his constitutional right to decline service as a conscientious objector. The Vietnam War was still supported by a majority of Americans at the time; Ali’s decision to speak out against it was hugely controversial, and he was pilloried by politicians and the media as a coward and traitor. “I ain’t got nothing against them Vietcong,” explained Ali of his motivations. “How can I shoot those poor people? Just take me to jail.”

Ali was acting not from fear but from the strength of his convictions, and he paid a heavy price. In March 1967, he was stripped of his heavyweight title, and that June he was convicted of draft evasion and sentenced to five years in prison. He was effectively banned from boxing for three and a half years, stripped of his passport and unable to obtain a license to box in any state. Sacrificing the prime years of his career cost him untold millions, leaving him in debt and leading him years later to fight well past the point when he should have retired, absorbing damaging blows that many believe led to the Parkinson’s disease he suffered from for the final three decades of his life.

Acting on his conscience made Ali into the quintessential model of the politically conscious athlete, and his influence was felt from Tommy Smith and John Carlos raising their black-gloved fists in protest on the 1968 Olympics medal stand to outfielder Curt Flood’s 1969 challenge against baseball’s reserve clause, which ultimately led to the free-agent era. His courage remains an inspiration to anyone acting on principle in defiance of prevailing public opinion today.